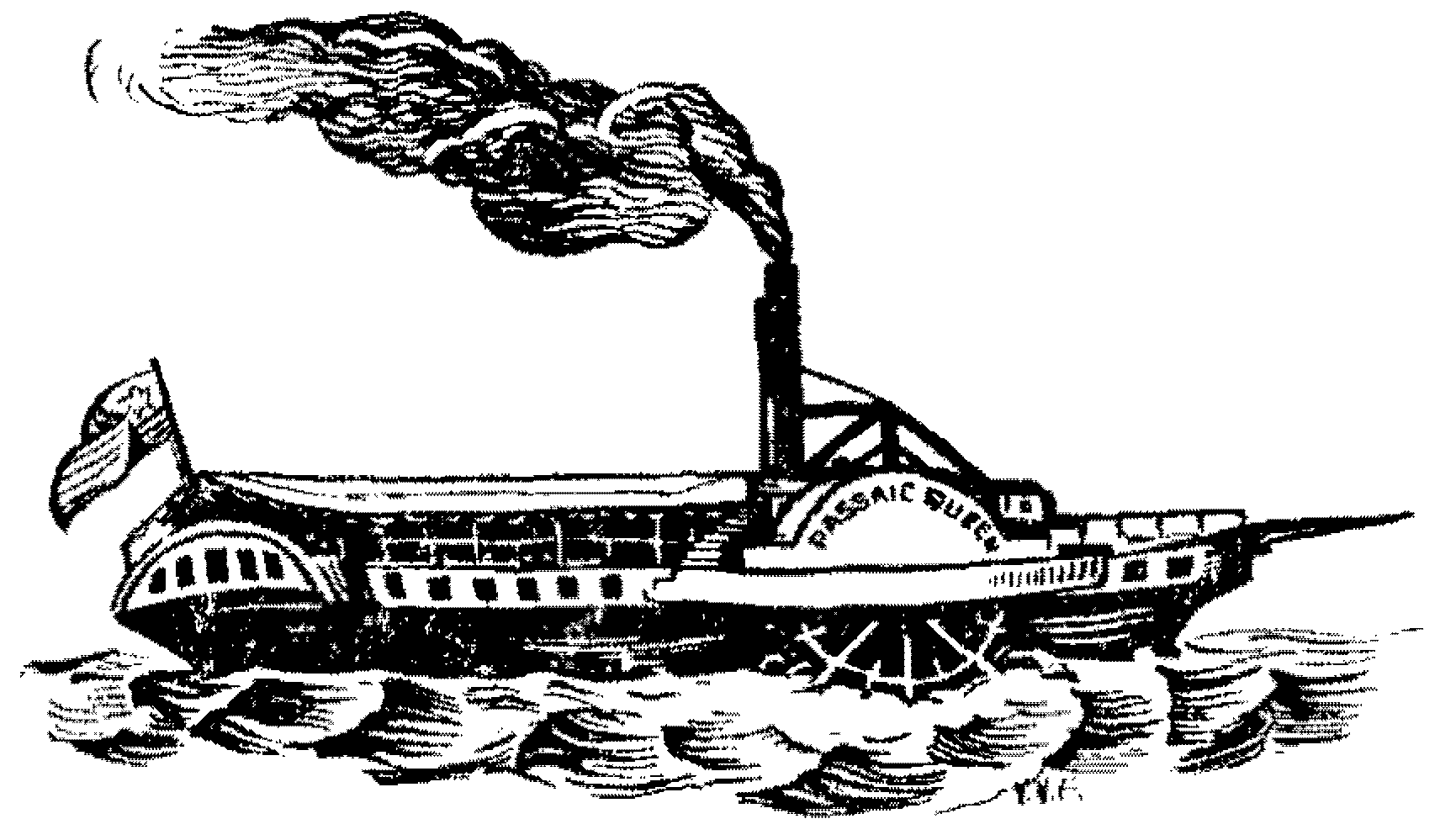

When Nutley Commuted by the “Passaic Queen”

FROM ARCHIE COE

THE “Passaic Queen” lived up to her name. She was regal; she was every inch a queen. Her lines were slim and her deck seemed to skim the water. By day there were flags and bunting, and by night paper lanterns to symbolize the merrymaking that befits a workaday boat turned excursion steamer.

Twice a day the boat steamed up and down the Passaic River between Passaic and Newark carrying passengers back and forth on her two round trips. The rest of the time, she ferried funmakers from Newark and the bay up to picnic grounds in the groves along the banks. Nutley was a favorite rendezvous with several groves as well as Feuerbach’s hotel, the old “Firebox,” where there were simple bucolic amusements under the trees.

You had only to stand on the deck and wave to bring the graceful “Queen” to your very shoetips, but the five-cent fare was dear. Interest was high here, among town boys who today are grown and aging men, when the echo of the slapping wheels preceded the vessel. “The ‘Queen’ is a-comin’,” went the cry and every barefoot boy in town within running distance of the river took to his heels to watch the boat glide by.

River boating is a tradition in Nutley, ever since the Indian canoe days of our colonial founders three centuries ago. But in the now dimming days when today’s men were yesterday’s town boys and the “Queen” made her last run on our river the “Penny Jigger” era ended and the street car rails were laid between Big Tree and Joralemon Street to connect Newark with Paterson.

Archie Coe of 212 Walnut Street is one of those who remembered the “Queen” and he was one of the last to see her when, “come down in life” after being dethroned from the Passaic, she ended her days as an excursion boat in New York Bay waters.

“When the tide came up the river, everyone went down to watch the ‘Queen’ steam up river to Passaic, but when the tide turned, the Passaic was an open sewer as all the filth of the valley above Nutley was swept downstream into Newark Bay,” Coe remembered.

“The ‘Queen’ was an amusement boat, even though it was run to carry passengers and freight between the two cities. In July and August it was frankly unpleasant to travel on or to live along the river. It is a historic fact that the air around the river was so bad that it took the paint off the houses that fronted on the Passaic.

“The last time I saw the ‘Queen’ was in the Hudson River during the naval parade that welcomed Dewey back home after his victory at Manila Bay at the end of the Spanish-American war. My sister took me by carriage and ferry to New York and we went out to see the warships.

“Suddenly my sister pointed to an excursion ‘boat and said ‘There’s the “Queen.”’ It was, sure enough, but she had come down in her career and was loaded with drunks who had their shoes off and dragged their feet in the water.

“I remember, though, when it ran on regular schedule up and down the river all day long. For many years Duncan’s Mills used to ship all their woolen goods by water and loaded at what was called Duncan’s dock at the foot of Grant Avenue. There was another dock at the foot of Nutley Avenue, and if you wanted to ride the ‘Queen’ either way, you merely stood on the dock and waved your handkerchief and the pilot would nose the craft over to pick you up.”

In the early days of river traffic, it was cheaper and easier to haul freight to New York by water than by road across the meadows. The stone which was quarried on both sides of Park Avenue was loaded on barges at a dock where the Avondale bridge now stands, then called North Belleville, and was floated to New York where it went into the building of the famous “brown stone” mansions of a hundred years ago.

Although the “Queen” was the last of the favorite river boats, she was no more glorious than many of her predecessors, the “Olive Branch,” the “Highland Chief,” the “Rockaway” or the “Belleville.” In those early days Nutley and Belleville were both a part of Bloomfield, but when they seceded to form the town of Belleville, they turned their eyes north and south to Passaic and Newark and the river provided the easiest means of travel.

A local historian of a century ago, Hugh Holmes, wrote a “History of Belleville” which applies to Nutley as much as it does to present-day Belleville, since the Belleville of his days combined both towns. Holmes played a big role himself in getting river traffic, and particularly commuting by boat, started. Having been a “river man” himself, he left the most coherent story of the busy Passaic, harnessed for transportation, of all the contemporary recorders.

The following is from his history: “The first boat that ever ran up the Passaic under its own power did so in 1838 and was called the ‘Olive Branch.’ The proprietor was R. L. Stephens of Hoboken. She was only about 70 feet in length. Her decks covered two small hulls, each one placed near the outside guard, thus leaving a space in the center for the wheel like the old style ferry boats. She carried both freight and passengers from Passaic to Newark and ran for one season.

“Captains John Young and Caleb Neagles were then running a line of schooners to New York and the latter bought a sidewheel boat called the ‘Wadsworth.’ He tried to get others to take a share in her but in this he failed, so he commenced to run her on his own account between here and New York but her machinery was not the best and her boiler old and the last trip she undertook, got as far as Newark. The steam was oozing out from her boiler in different places and when she struck the dock, so did her passengers without waiting for the gangplank. Her freight was reshipped to New York.

“Then Darius and Mathias Williamson, twin brothers, who had bought property here concluded to build a small boat and be captain, pilot, engineer, deck hand all by themselves, and thought by so doing they could make it pay. They did build, but so small that when they placed the engine and the boiler in her she sank to the gunwails in the water and there was no room for the freight or passengers.

“Then Abraham Zabriskie of Saddle River concluded to build a light draught boat and give her all the bearing possible yet to go under the bridges; placed a wheel in the stern. She was called the Proprietor, and was a nice boat for her kind. She was also for freight and passengers between Passaic, Belleville, Newark and New York and her trips to be every other day. He had store houses built on different docks for freight. We all thought she would at least be an alternate day success, but from some cause she was withdrawn after running two years.

“Then came Captain Bancroft with his boat called the Gilpin, a sidewheel 125 feet keel to make daily trips to New York with freight and passengers. Her boiler was not large enough and had to carry such a head of steam that the engineer, Harry Clayton, one of the best, would say to the writer, ‘Thank God, we are safe through another day.’ But she did not earn enough to satisfy the captain and owner.

“In 1856 Captain William Tupper brought to our place a beautiful little sidewheel steamer called the Rotary which had been built to test a rotary engine, invention of Mr. Barrows of New York, which he thought was a success and wished the public might witness its workings. But Captain Tupper had taken that out and put in two oscillating engines and changed the name to Governor Kembal.

“At that time there was no communication to New York, or yet to Newark, except by stage or on foot and as some other mode was greatly needed and as Captain Tupper had offered to sell the ‘Governor Kembal’ for $5,500 a meeting was called at the office of H. K. Cadmus with the following gentlemen present: J. Eastwood, S. H. Terry, Doctor A. Ward, G. DeWitt, H. K. Cadmus and the writer. At that meeting these gentlemen agreed to raise the amount by subscriptions, making a stock company and buy the steamer.

“The next month, the Legislature being in session, the writer was appointed to obtain a charter. Thus was incorporated the Belleville Steam Boat Company. A board of directors was elected and S. H. Terry was appointed treasurer and the writer, secretary. She was called ‘Belleville’ and was a picture, a little floating palace. On April 13, 1857 she made an excursion trip up the river with the stockholders and invited guests. All were delighted with the trip and the steamer the next day made her first regular trip to Newark in 30 minutes.

“The writer soon found out by being secretary that it meant captain, pilot and deck hand, for if any were absent he had to take his place.

“If the boat was not on time, he had to drive along the river to know what was the cause, or if she missed a trip which she sometimes did on account of the tide, he must have some good reason to give in his report to the directors who met monthly. And, why not! He was getting a salary of fifty dollars per year.

“The boat was run successfully for two seasons, and over 60,000 passengers carried and a good route established for some one, which was the desired object. Captain Martin, who was then running the steamer Tamenend from Newark to New York made a proposition to buy the Belleville, with the understanding that the next season he would put on a boat more commodious. With this understanding the company sold her to him in 1859 for the small sum of $2,600, $575 in cash and 45 shares of the Morris and Essex Railroad stock at ninety cents.

“Captain Martin continued to run the boat that season, but like many others became financially embarrassed.

“The first of the next season we were without any boat when Captain Charles Field brought on the river a sidewheel steamer called the Highland Chief and on June 8th made her first trip. He continued to run her through the excursion season and then concluded to take her away, but proposed to sell and tried to get different parties interested but failed. Finally the writer, not wishing to see her taken from the river, bought her and gave a large 200 ton schooner as part payment.

“This was the fall of the great political campaign of 1860, and many meetings of both parties were held in our place, when she brought a full cargo of 600, first of ‘Wide Awakes’ and then again as many more of the ‘Hickory Boys.’ It was a dark night when they came up the river with their torches burning, looking as if they might be a delegation from the lower regions.

“In the spring the first trip was made on the evening of March 26, 1861, an excursion to Newark free to all parties who would buy a ticket to hear P. T. Barnum lecture in the Opera House, for the benefit of the M. E. Church of this place. He called the boat Confidence, hired a grove up the river, trimmed it up nicely, put up tables, swings, laid dancing floors and had all conveniences for parties.

“This year was the commencement of the War and most of our military company under the command of Captain Aaron Young offered themselves in their country’s service to help put down the Southern rebellion. The boat took them daily and the owner was told to keep an account and it would be paid. It amounted to over $100 and the amount is yet unpaid.

“Then sometime after the Confidence was taken off the river (she having also carried freight in connection with the Stephens and Condit’s line to New York). Some parties from Passaic put on a sternwheel boat to run from that point to New York as a freight boat, called the Lodi. She ran in one day and returned the next but it did not prove a success.

“At the time the Confidence was sold, there was a charter granted for a horse-railroad and all eyes were turned to it thinking that would supply our need, but they were to run to the north end of our town. Instead they had only brought it to the south side of the Second River, to what was then called Flanigan’s station and for six years through mud, snow, slush, rain, heat and dust, all had to foot it and then pay ten cents for a ride the balance of the way. He announced that he would give $100 per annum to anyone who would put on and continue to run a suitable boat and hoped others would do the same. But there was no second to the proposition. Instead they wanted him to put it on the river.”

Mr. Holmes finally made a proposition that if 100 commuters would pay $35 each for the season for two years he would undertake another boat. He specified two years because he felt that the Railroad Company would come to terms after that time. The meeting acclaimed this most satisfactory. Fifty signatures were obtained at the meeting and a committee appointed to get the rest. On the strength of this showing Mr. Holmes took an option on Rockaway, the one best adapted to the river. However at the meeting when the 100 signatures were to be in only 85 were brought forth, along with the assurance that the other 15 would be forthcoming.

“With this assurance the bargain was closed and on May 6th brought the ‘Rockaway’ to Belleville. On the 20th she was inspected and took a sail with invited guests. The next day she started on her first trip with Charles Couse as engineer and C. W. Lee as captain.

“In order to help make the boat pay, he did as he did with the Confidence, hired two groves, drove wells, put down dancing floors, put up tables, swings, and all conveniences for parties catering for excursions.

“There was but two feet of water on the reef at low tide and the boat drew two feet six inches, and he was compelled to do as he had told them he should, make time tables to suit. Even so the tides would catch him and he had to convey his passengers from the reef in carriages. The boat made one run from Passaic, two from North Belleville and six from Belleville to Newark daily.

“After all was working satisfactory he called on the chairman of the committee for his 100 notes of $35 each. There was to be some single ones at $25. What was his astonishment and disappointment, when he was told they had but 42.”

Mr. Holmes felt that he had been deceived, for he had invested at least $25,000 based on promises. Nevertheless he made the best of it.

“Because the reef was a great obstruction to all navigation and particularly so to steamboats, and some had told him they would help him if he would get it deepened, he made an agreement with Morris and Cummings to give him five feet of water at low tide, fifty feet wide over the whole reef for the sum of $1,200. They worked on it for 24 days without any benefit, for some parts were as shallow as before. Then they threw it into day’s work at $100 per day and demanded $2400. Those who promised him aid when there was money to pay were not there. He was alone and when they threatened suit he told them to go ahead. They never pressed the claim.

“Then he went to the Honorable G. A. Halsey, who was in Congress, to try and get an appropriation to clear the reef. General Newton was instructed to make a survey and estimate. He came to Newark. The writer in a steamer took him over both reefs. His report was that it would cost $80,000. Mr. Halsey got that year an appropriation of $25,000 to start and afterward the balance. The work was done and today any vessel that can get to Newark can reach the docks at Belleville.

“The Rockaway ran the season through by the careful management of James Black, who was pilot and Charles W. Lee, captain and carried nearly 50,000 people, averaging three excursions per week without any serious accident. One day she came home minus a smokestack. The draw on the Delaware, Lackawanna Railroad bridge did not get off in time, and the stack was carried away.

“There have been quite a number of steam tugs on the river for towing vessels and very many small pleasure and family steam yachts, and for the last four years the small propeller Passaic Queen for the summer months has been making two trips a day with passengers from Newark to Passaic. But one of the great objects for which the boats were started was accomplished. “The horse railroad company was brought to terms. They commenced almost immediately to extend their road and soon finished it and notwithstanding all the protestations against it before the boats were placed on the river; scores and scores daily were forgetful of their promises and took to the cars.”